There isn’t a writer in the world who hasn’t felt the pang of poorly edited work.

Whether it is a student paper declaring nebulously in red ink, “Be Clearer” (big help, thanks), or an essay that reads like someone else wrote it entirely, all writers endure unhelpful feedback from time to time.

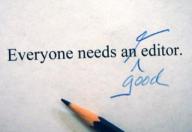

The irony is that most writers are also guilty of dishing out unhelpful feedback. When we edit someone else’s work, the temptation is to see it through the lens of how we would do it, and this creates a hindrance to editing well. This is not to say that the writers are not talented; they might be able to turn a phrase prettier than a pansy, but that means very little when tasked with editing someone else’s product. It comes down to this:

WRITER MINDSETS ≠ EDITOR MINDSETS

Obviously, there is overlap between writers and editors. Many writers can be great editors and editors can be great because they understand the experience of writing. But we are talking about a Venn diagram here–two separate categories of thinkers who only occasionally overlap.

Why so little overlap? Let’s turn back time to two courses I took in college, the worst and the best. The worst class was taught by a professional writer-in-residence. I had read her books and they were awesome, so I arrived to the first class eager to learn. Twenty minutes in it was obvious she had no idea why she was an accomplished writer. She had very little to say about style, technique, research strategies, or successfully engaging an audience. What she achieved had been through blind instinct, and she therefore had little instruction to endow in spite of her considerable experience.

By contrast, the best course began its first day by illustrating how readers and writers think differently. Writers set out to organize ideas and get them down on paper in pretty arrangements. The difficulty is that ideas are nouns…things…stuff. Readers read for meaning; they want to know what’s happening, what’s moving, what’s changing. Readers watch for verbs. Given this, we were told that the key to great writing lies in the writer’s ability to write the way readers read best, i.e. through action and change.

Extrapolating from both of these experiences, I see two pillars of great editing: first, great editors understand why a piece of writing works or doesn’t work, and second, they successfully bridge the gap between how writers write and readers read.

For this first pillar, editors need to be aware simultaneously of the big picture points, the minutia, and the relationship between the two. It is this balance that allows them to make wise decisions about any changes they make to someone else’s work. It serves no purpose to change something at the sentence level unless it serves the paragraph’s aims. It makes no sense to delete or move a paragraph unless there are demonstrable reasons to do so. Good editing points to concrete reasons for why changes A, B, and C achieve the writer’s goals.

Notice: the writer’s goals. The writer most likely had good purpose in setting out to write, whether or not he executed his goals well. This brings me to the second pillar of good editing: the editor is the writer’s advocate, not his competitor. The editor stewards the writer’s voice. She is an ambassador of the writer’s words, making sure they resonate with the audience. Ambassadors say things their country’s president would say, not what they would say if they were president. They only tailor the message if and only if the audience will struggle to understand.

So how to become a good editor? There are several practical steps to take.

- When sitting down to edit someone else’s work, remember that you are not rewriting it, you are editing it. This is an entirely separate skill from writing, a completely different hat to wear. You will be using many of the similar tools of a writer, but you will NOT apply your own voice and you will NOT change things just because that is how you would do it. Instead, you will focus on strategy, reason, and resonance with the audience on the writers’ behalf. Make sure you know the reasons behind everything you change. If you don’t have a reason, don’t change it.

- When you get a new piece to edit, refrain from making any changes until you’ve read the entire piece. Sit on your hands if you need to. But don’t touch it until you’ve read it as a reader would read it. Imagine it were already published, in a newspaper or magazine or book. Imagine you were simply consuming it…how would you take it? What confuses you? What made you slow down? Keep a mental–or physical–note of difficulties you experienced as a reader. Then on your second go through, return to these areas and ask yourself, “What might make it smoother or more persuasive?” Stick to Occam’s Razor as much as you can, as often times a simple move like cutting a word or rearranging some sentences will solve the problem much better than trying to rewrite it without the writer’s notes in front of you.

- Ask the writer questions. Don’t think you need to solve his problems blindly. If you are having difficulty divining the writer’s intention with a sentence or concept, just ask him about it. You are partners, after all. Ask him to rephrase things, or to explain it as if to a novice. Often both you and the writer will stumble across simpler ways of communicating ideas than either of you thought of in the first place.

To sum up, editing is not about passing the torch to another writer. It is an entirely different skillset. If you have a good editor in your life, go and give them a hug. And a cookie.

What Good Editors Do

There isn’t a writer in the world who hasn’t felt the pang of poorly edited work.

Whether it is a student paper declaring nebulously in red ink, “Be Clearer” (big help, thanks), or an essay that reads like someone else wrote it entirely, all writers endure unhelpful feedback from time to time.

The irony is that most writers are also guilty of dishing out unhelpful feedback. When we edit someone else’s work, the temptation is to see it through the lens of how we would do it, and this creates a hindrance to editing well. This is not to say that the writers are not talented; they might be able to turn a phrase prettier than a pansy, but that means very little when tasked with editing someone else’s product. It comes down to this:

WRITER MINDSETS ≠ EDITOR MINDSETS

Obviously, there is overlap between writers and editors. Many writers can be great editors and editors can be great because they understand the experience of writing. But we are talking about a Venn diagram here–two separate categories of thinkers who only occasionally overlap.

Why so little overlap? Let’s turn back time to two courses I took in college, the worst and the best. The worst class was taught by a professional writer-in-residence. I had read her books and they were awesome, so I arrived to the first class eager to learn. Twenty minutes in it was obvious she had no idea why she was an accomplished writer. She had very little to say about style, technique, research strategies, or successfully engaging an audience. What she achieved had been through blind instinct, and she therefore had little instruction to endow in spite of her considerable experience.

By contrast, the best course began its first day by illustrating how readers and writers think differently. Writers set out to organize ideas and get them down on paper in pretty arrangements. The difficulty is that ideas are nouns…things…stuff. Readers read for meaning; they want to know what’s happening, what’s moving, what’s changing. Readers watch for verbs. Given this, we were told that the key to great writing lies in the writer’s ability to write the way readers read best, i.e. through action and change.

Extrapolating from both of these experiences, I see two pillars of great editing: first, great editors understand why a piece of writing works or doesn’t work, and second, they successfully bridge the gap between how writers write and readers read.

For this first pillar, editors need to be aware simultaneously of the big picture points, the minutia, and the relationship between the two. It is this balance that allows them to make wise decisions about any changes they make to someone else’s work. It serves no purpose to change something at the sentence level unless it serves the paragraph’s aims. It makes no sense to delete or move a paragraph unless there are demonstrable reasons to do so. Good editing points to concrete reasons for why changes A, B, and C achieve the writer’s goals.

Notice: the writer’s goals. The writer most likely had good purpose in setting out to write, whether or not he executed his goals well. This brings me to the second pillar of good editing: the editor is the writer’s advocate, not his competitor. The editor stewards the writer’s voice. She is an ambassador of the writer’s words, making sure they resonate with the audience. Ambassadors say things their country’s president would say, not what they would say if they were president. They only tailor the message if and only if the audience will struggle to understand.

So how to become a good editor? There are several practical steps to take.

To sum up, editing is not about passing the torch to another writer. It is an entirely different skillset. If you have a good editor in your life, go and give them a hug. And a cookie.

Share this:

Leave a comment

Filed under Inspiration and Creativity, Running Commentary on whatever tickles the fancy

Tagged as editing, editors, emilycapo, how to, how to edit, writing